December 14, 2025

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights (IOHR) said that the issue of internal displacement in Iraq has reached a critical crossroads, more than a decade after the outbreak of its largest waves, amid a reality still marked by fragility and the absence of sustainable solutions. This comes at a time when former Iraqi President Barham Salih has assumed the position of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

IOHR views this development as an important political and human rights opportunity to bring the suffering of internally displaced Iraqis back to the forefront of international attention—not as a temporary humanitarian emergency, but as a prolonged structural issue rooted in governance failures, post-conflict policies, and weak social and legal protection systems.

Monitoring teams from the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights describe conditions in displacement camps as environments unfit for dignified human life over the long term. What were intended as emergency solutions have, in practice, become semi-permanent places of residence for thousands of families. The vast majority of tents remain made of lightweight materials that provide little protection from extreme heat in summer or harsh cold in winter, rendering daily life physically and psychologically exhausting, particularly for children and the elderly.

Estimates obtained by IOHR through field monitoring and direct interviews indicate that a significant proportion of displaced families have spent more than five years living in tents, while some have endured nearly a full decade without any real transition to permanent housing. Displaced persons interviewed by IOHR stressed that the tent—meant to be a temporary shelter—has become a daily reality devoid of privacy, stability, and the most basic conditions for normal family life.

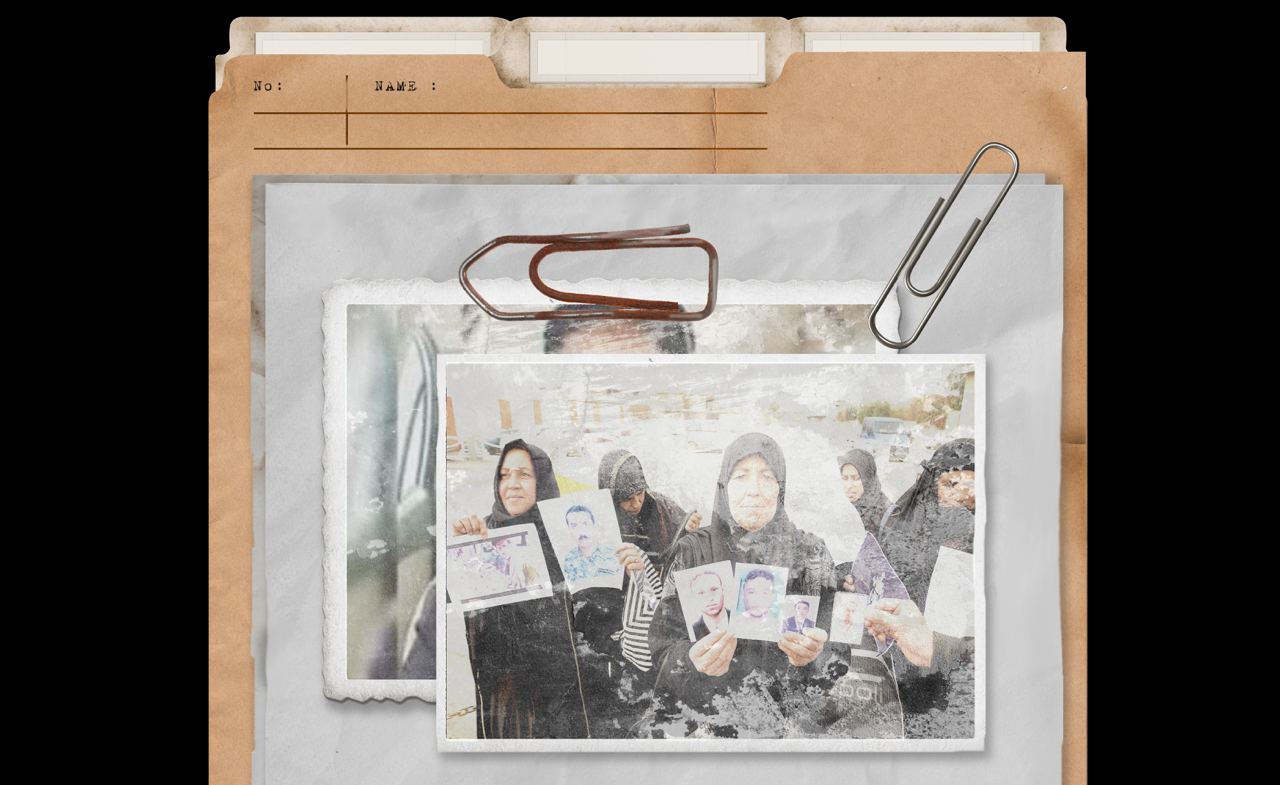

Since 2014, IOHR has systematically monitored internal displacement in Iraq through field observation teams, direct engagement with displaced families, and ongoing assessment of camps and return areas. The Observatory has also documented patterns of violations associated with displacement, including non-voluntary returns, denial of access to basic services, loss of civil documentation, social discrimination, and the absence of sustainable livelihoods.

Over the years, IOHR has found that displacement in Iraq has not been a fleeting phenomenon limited to the war against ISIS, but rather a long-term social reality that has reshaped the lives of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.

Data and assessments gathered by IOHR through direct monitoring and cross-referenced with local and governmental sources indicate that large numbers of displaced people continue to live in unstable conditions—either in camps that were formally closed without the provision of genuine alternatives, in host communities lacking adequate infrastructure and services, or in return areas suffering from security fragility, limited employment opportunities, and weak health and education services.

These findings also indicate that a substantial share of what is classified as “return” in recent years has not been driven by genuine improvements in living conditions, but rather by reduced assistance, economic pressure, or fear of remaining in camps with no future prospects.

In this context, IOHR Head Mustafa Saadoon stated that the appointment of an Iraqi figure to a senior international position responsible for refugees and displaced persons should be understood as carrying a heightened moral and political responsibility toward Iraqis who continue to bear the burden of displacement.

“Displacement in Iraq is no longer a temporary issue tied solely to wartime conditions; it has become a deeply entrenched social reality,” Saadoon said. “Children have been born in camps, young people have grown up without stability, and families have lost trust in repeated promises. These are not numbers—they are entire lives suspended in uncertainty. Today, with former President Barham Salih assuming this role, we hope that the Iraqi displacement file will be reopened with genuine seriousness, and that the voices of the displaced will be reflected in international policymaking as an unresolved, ongoing issue.”

Saadoon added that the international community must move beyond managing displacement toward addressing its root causes through a rights-based approach that guarantees voluntariness, safety, and dignity, and holds accountable any policies that effectively reproduce vulnerability or impose unsustainable returns under administrative pretexts.

IOHR’s data further show that many camps suffer from severe shortages in sanitation systems and access to safe drinking water. In some locations, dozens of families share limited sanitation facilities, significantly increasing the risk of skin and gastrointestinal diseases, particularly during the summer months. Displaced persons have also reported frequent disruptions in water and electricity supply, or access limited to only a few hours per day.

IOHR estimates that a substantial proportion of school-aged children in camps face partial or complete interruption of their education, due to the distance of schools, shortages of teaching staff, or the need for families to rely on child labor to meet basic needs. According to the Observatory, this reality risks producing an entire generation that has grown up outside the formal education system, compounding the long-term consequences of displacement.

The Observatory has also documented that many families live in camps without complete civil documentation, either because documents were lost during displacement or because of subsequent difficulties in reissuing them. This situation restricts access to healthcare, education, and social protection, and leaves families in a state of prolonged legal vulnerability.

IOHR concludes that prolonged residence in tents for many years is no longer merely a humanitarian concern, but a clear indicator of the failure of public policies to transition from emergency response to sustainable solutions. These tents, with all their inherent fragility, reflect a displacement crisis that has not been addressed at its roots and continues to leave hundreds of thousands of Iraqis trapped in an open-ended state of waiting.

The Observatory added that its recent field data reveal a more complex reality than that reflected in general reports. Many families who left camps did not do so because they had secured durable solutions, but because they could no longer endure life amid declining assistance and lack of options.

“What we are witnessing today is a shift from visible displacement to invisible displacement,” IOHR said. “Families are living on the outskirts of cities or in ill-prepared return areas, without legal protection or service guarantees. This form of displacement is less visible, but more dangerous.”

IOHR noted that women and children are the most affected by this reality, with increasing rates of school dropout, declining access to healthcare, and heightened risks linked to poverty and precarious work.

For his part, IOHR Head of Monitoring Meetham Ahmed stated that the continuation of this situation raises serious legal concerns regarding the Iraqi state’s obligations toward its citizens and its international commitments related to internal displacement.

“Iraq is constitutionally obligated to protect the dignity of its citizens and internationally bound by principles of voluntariness, non-coercion, and the guarantee of safe and dignified return,” Ahmed said. “Any policies that result in the closure of camps or push people to return without genuine security, service, and legal guarantees place the state under direct legal responsibility and may amount to clear violations of international standards.”

He added that the absence of clear legal frameworks for managing return, coupled with failures to guarantee civil documentation, housing, and livelihoods, leaves thousands of families in a dangerous legal vacuum that threatens their fundamental rights and risks reproducing the very causes of displacement.

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights believes that Barham Salih’s assumption of the role of High Commissioner for Refugees could mark a turning point if it is used to refocus serious international attention on Iraqi displacement—linking humanitarian response with long-term political and economic solutions, and reaffirming that displacement is not an inevitable fate, but the result of policies that can and must be corrected.

IOHR stresses that ending displacement in Iraq requires genuine partnership between the federal government, local authorities, and the international community, under effective UN oversight that ensures displaced persons are not left facing two equally harsh options: prolonged vulnerability or forced return. Protecting the rights of displaced people today, the Observatory concludes, is a true test of the credibility of the Iraqi state and of the core principles of the international system tasked with protecting human dignity, wherever it is at risk.